June 2016 | Volume XXXIV. Issue 3 »

Why Outcomes Matter: An Update on PLA’s “Project Outcome”

June 8, 2016

Carolyn Anthony, Skokie Public Library

A young woman who had recently graduated from college came to see me as part of her exploration of possible career directions. “I feel like in public libraries I could really make a difference in people’s lives,” she said. I told her I agreed, but had to acknowledge that as of yet we have little data to confirm the hypothesis that public libraries do, in fact, change lives. In a recent study from the Pew Research Center, it was reported that two-thirds of Americans (65 percent) ages 16 and older say that closing their local public library would have a major impact on their community. In an earlier study, the Pew Research Center reported that 90 percent of Americans ages 16 and older say that the closing of their local public library would have an impact on their community.

If closing the public library would have an impact on the local community, does it follow that the library also makes an impact by being open? We have a lot of anecdotes about transformative experiences at the public library, but no real data to back that up. Do the stories represent occasional, exceptional outcomes of library use or are they part of a pattern that in fact points to broad community impact?

For years now, public libraries have largely reported output measures of activity such as circulation, reference questions answered, door count, and program attendance. These measures show that the library has put resources to use, and the measures may be compared over time within a library to show a trend in library use or compared among libraries of similar size and funding level to get an idea of the potential for growth in services. The output measures, however, do not begin to answer the question, “What difference did the public library make to the individual?” or the larger question, “What is the impact of the public library on the community?”

Moreover, in recent years, many of the output measures traditionally reported by the public library have started to decline. We understand that public libraries are fielding fewer reference questions because so many people are using Google to find answers to their questions. They may be reading some of their books and magazines digitally and renewing titles online rather than making a trip to the library to have staff update their circulation record. For these reasons and more that we are aware of and can explain, library outputs are generally static or declining. Funding authorities may look at these figures and conclude that the local public library needs less revenue for operations or that there is no need to expand or upgrade a dated library facility.

Those of us working in public libraries know that we are not doing less. In fact, public libraries have been busier than ever and doing important work such as helping job seekers prepare resumes or look for work during the recent downturn in the economy; working with parents and preschoolers on early childhood literacy skills; teaching people computer skills; and bringing people together for discussion of societal issues such as immigration or prison reform. Unfortunately, we have not done a very good job of capturing the results of these efforts. The number of people served has been collected via hash marks and reported in a larger figure of library program attendance or door count that tells nothing about the difference the service made to the individual or collectively to the community.

FRAMING THE WORK

How you frame what the library does matters. It shapes public perceptions of the library and its services. If library programs are seen as simply entertaining and fun, it is easy for funding authorities to cut the revenues for the library in tight times. If, on the other hand, the library can show that library programs contribute to essential learning, it will be easier to garner support for the library and its programs. Valerie Gross, director of the Howard County Public Library in Maryland, is a strong proponent of emphasizing the educational function of the public library and has been very successful in ensuring sustained funding for the library system. In Howard County, education may be the primary concern, while in another community it may be that health, economic development, workforce development, or immigrant integration is foremost in the minds of government officials and community leaders. As Amy Garmer notes in a recent Aspen Institute report, aligning library services in support of community goals is the primary strategy for success in public libraries. Being able to show that library programs contribute to individual outcomes and have an impact on the broader community in areas of essential concern is critical.

I successfully ran for the office of president of the Public Library Association (PLA) in 2012 on the platform of the need to adopt a system of outcome measures for public libraries so that we could begin to show the true impact of essential library programs and services. In 2013, the PLA Executive Board appointed a Performance Measurement Task Force to begin the development of simple surveys that all public libraries could use to measure outcomes, enabling PLA to begin to compile data for use in advocacy on a larger scale. The task force has been chaired by Denise Davis of the Sacramento Public Library and former director of the Office of Research and Statistics at the American Library Association. The composition of the task force includes a state librarian, a state data center coordinator, and representatives of public libraries of different sizes throughout the United States; advisors include public library researchers John Bertot, Joseph Matthews, and Carl Thompson.

WHAT AND HOW TO MEASURE

So what are outcome measures? Outcome measures assess the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavior brought about by participation in a program or service. Some outcomes may be easily observed as in the case of the demonstration of a skill. For example, you might teach a finger play at a preschool storytime and observe that ten of the twelve children are able to sing the lines and execute the finger play by the end of the program. That’s an outcome you could report, noting that 83 percent of the children attending the session acquired the skill of performing the finger play, an important step contributing to preschool literacy and kindergarten readiness. An example with adults might be the number of people who successfully download an e-book to a reader or tablet after being shown the appropriate steps.

Of course, it can be hard to observe and make notes on performance while you are simultaneously conducting the program, answering questions, and helping people who are struggling to learn the demonstrated skill. It can be a great help to have a second staff person or volunteer who can make such observations and record the results. Librarians definitely need more than the program instructor simply reporting back that “everyone was on board and the program was a big success.” Outcome measures assess the learner’s perspective on gains from the program or service. To get direct feedback from program participants, the task force decided to implement a series of simple surveys to capture the needed information. The surveys can be completed by participants quickly at the end of a program or after receipt of a service. In the case of young children, a parent or caregiver may be asked to complete the survey on behalf of the small child.

The task force developed surveys in seven areas of essential library service including:

Civic/Community Engagement

Digital Learning

Early Childhood Literacy

Economic Development

Education/Lifelong Learning

Job Skills

Summer Reading

PUTTING RESULTS TO WORK

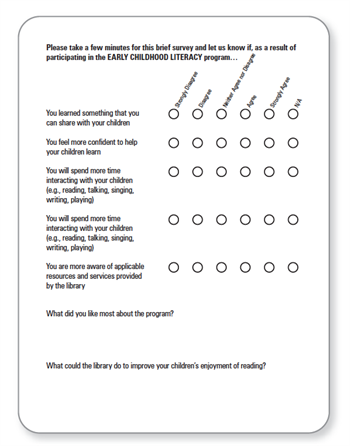

The surveys each have just six questions. Four questions ask the participant to choose on a five-point Likert scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree” whether they learned something new from the program or service, increased their confidence in the subject area, anticipate a change in their behavior, and have increased awareness of library resources in support of the subject. The other two questions are open-ended, asking for general feedback on the program and suggestions for improvement. The following example shows a survey that could be given to parents of young children following a parent/child early literacy program.

The surveys were completed and field tested in 2014. Testing and subsequent experience have shown that people are very willing to complete these brief surveys that can be administered in print or digital form. The work caught the eye of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which provided generous funding support to enable PLA to accelerate the project. As a result, PLA built online resources and support tools around the task force’s work and Project Outcome was officially launched in June 2015.

The Project Outcome website, www.projectoutcome.org, was designed to easily guide public library staff through the outcome measurement process, from choosing appropriate service areas for measurement to scheduling the surveys, inputting the responses, analyzing the results, and using the results to take action. Project Outcome is a free service for all public libraries in the United States and Canada. The three-year funding runs through the end of 2017 and PLA is committed to continuing Project Outcome beyond the term of the initial grant, adding it to the list of ongoing successful PLA products such as Every Child Ready to Read and Turning the Page.

Since its initial launch, Project Outcome has had over 1,400 participants register from over 900 public libraries across all 50 states in the United States and Canada. Nearly half of Project Outcome’s libraries are already using the survey tools within their library and have collected over 11,000 patron surveys. For the first time, public libraries, whether they are new to outcome measurement or advanced in data collection, have free access to an aggregated set of performance measurement data and analysis tools they can use to effect change within their communities and beyond.

Results from the surveys have already been used by participating libraries to revise and refine programs, to allocate resources to priority areas with demonstrated outcomes, and in advocacy to tell the library’s story and obtain support. Use of outcome measurement fits neatly within the strategic planning process in which one starts with determining goals and objectives answering such questions as: What do we hope to accomplish?Why are we doing this activity? How will people benefit? Who will benefit? In strategic planning, representatives from the library board, staff, and community consider current community needs and the library’s capacity to respond to those needs, addressing the question, where can the library have the most impact on the community? Project Outcome surveys will help the library measure its success in accomplishing the strategic planning objectives and make any needed mid-course corrections.

PLA’s Performance Measurement Task Force continues to meet and work together to help libraries of all sizes measure outcomes successfully. Members of the task force have developed and are in process of testing follow-up surveys to be given to patrons three to six weeks after a program or service to determine whether participants were able to apply knowledge gained as anticipated and whether they have indeed changed their behavior as a result. For example, someone may attend a library class in digital learning on the software Microsoft Publisher with the intent of producing a brochure for their organization or business. The patron may feel they learned new skills and leave the class feeling confident about their new skills, responding accordingly on the survey following the program. But were they able to apply the knowledge, combine the skills, and produce a brochure as planned? The follow-up survey provides a second opportunity for the library to collect data on the effectiveness of its programs. Another example of a change in behavior might be that a parent reports reading more frequently with their young child or incorporating singing, talking, and playing in everyday interactions with their child as a result of attending

a parent/child storytime at the library.

Project Outcome is being crowd-sourced, evolving in response to feedback from libraries as the various components are rolled out. The Project Outcome follow-up surveys will be introduced at the ALA Annual Conference in June 2016. Further work is planned to assist libraries that want to work on data collaboration with partner agencies, such as local schools, as well as guidelines for libraries that want to write their own outcome measures. States and other regional agencies have come forward looking to roll out Project Outcome throughout their networks. Affiliate groups have been created among participating libraries for those who want to share implementation techniques and results with each other. What seems clear is that public librarians are eager to take this next step, to learn just how library programs make a difference in their communities, and how they can use outcome data to be more effective advocates. As ALA’s public awareness campaign states, public libraries do indeed transform individuals and communities, and now with Project Outcome we can demonstrate the ways that transformation is occurring.

1. John B. Horrigan, “Libraries at the Crossroads,” Pew Research Center, 9/15/2015.

2. Kathryn Zickuhr, “From Distant Admirers to Library Lovers—and Beyond,” Pew Research Center, 3/13/2014.

3. Amy K. Garmer, “Rising to the Challenge: Re-Envisioning Public Libraries,” The Aspen Institute, October 2014.

iREAD Summer Reading Programs

iREAD Summer Reading Programs Latest Library JobLine Listings

Latest Library JobLine Listings